- Home

- Pamela Moore

Chocolates for Breakfast Page 9

Chocolates for Breakfast Read online

Page 9

“Courtney! Courtney Farrell!”

“Hi, Barry.” She went over to him. She had no choice.

“Christ, I haven’t seen you in two months. Here, have a cup of coffee.”

Barry was a difficult man to predict. He had not seen Courtney for two months; the threat that the girl had once presented was forgotten. So much had transpired in the meantime; so many new threats and demands had been fled from, that he no longer felt the need to ignore Courtney. He disliked litigation, and he disliked hurting people. Courtney’s absence had mitigated the threat of possession and a real relationship, and he was pleased that he could relax.

“Well, tell me what you’ve been doing with yourself? How is Beverly Hills High?”

“Oh, it’s ghastly, Barry.” He had not asked her about her mother, and that was the natural question. He understood that if Sondra had disappeared from sight there was a reason for it, and the reason probably was that she was broke. So he did not embarrass the kid; these things were understood. Everyone knew that she did not get the part in Russell’s picture, and everyone knew that the Garden had impounded their clothes. But then, the cellar of the Garden was full of impounded belongings.

“I didn’t think you’d like it,” he said. “You’re so much older than kids your age, and the kids out here have lived a lot less than you have. That’s not as true at boarding school.”

“Yes, you’re right, Barry. Christ, it’s good to talk to somebody. I’ve missed being around here.”

As she talked to him, she thought, I’m going to go on talking to him. I’m not going back to that room for a long time. I’m going to make him want to stay with me. And she remembered what she had heard an actress who had become a symbol through attractiveness to men say to her mother, “When I’m with a man, all I think is sex, sex, sex.” She decided that she would try that.

“Tell me, Barry, what have you been doing with yourself? I read that you were on a couple of Kraft shows.”

“Yes, I did two, and I’m doing another week after next. My work is really picking up, now, with television. I haven’t much of a part, but it isn’t really bad. It’s the part of this taxicab driver. You see, when the thing opens, this girl is in the cab, and she says to the driver, ‘Take me anywhere, just anywhere. Drive around the city.’ And as he takes her through the city—it’s about three in the morning—he starts to talk to her, to find out why . . .”

As he talked, Courtney watched his face, and she thought: I’d like you to kiss me, yes, I’d like that very much; your mouth is so full and petulant, and your body is very slim, your hands gentle and sensitive—and as she imagined, she ran through the daydreams she had about him, only now he was here, and she was looking at him, beside him, and the attraction that she first found with Al was there, the attraction that made her drop her fork that day.

“ . . . but the girl is convinced that her brother really didn’t murder this guy, so she has gone to the apartment . . .”

Jesus Christ, Barry thought as he talked, this girl is all woman. She’s a real lovely young woman; this is no kid.

He felt the question, the searching, under the veil of conversation, and he found himself reciprocating.

Suddenly Courtney felt as though a wall had been removed. She was speaking wordlessly, and he heard her and was answering. She was no longer throwing her emotion against a block; he was reciprocating, and they were touching at a distance.

“But you’re probably bored with this, anyway,” he said. “Look, we’ve both finished our coffee, why don’t you come up to my apartment for a drink?”

It had worked, by God; she knew it would. She didn’t need the words of the actress to convince her that it would work; she sensed that she would win this man’s interest, and that was all she wanted. She would never forget that first day, when she found that it worked.

“Barry, I would love a drink. You know, I’ve never seen your apartment?”

“No,” he said. “I guess you haven’t.”

The apartment was well furnished, and somehow reminded her of Al Leone’s apartment. Al wouldn’t like her coming here. But the hell with Al.

“Is a martini all right?”

“I’d prefer Scotch—”

“You’ll drink a martini, by God, because that’s all I have.”

“Okay,” she grinned.

The apartment was not dim. Barry hated dimness. The door was open onto the balcony that ran on three sides around the pool, and the late afternoon sun was coming in. Her mother would think that she was staying late at school. She had done that sometimes, she had sat beside the big, ugly football field until it was dark, and her mother no longer worried, because she respected Courtney’s moods. After all, she could not blame the girl for hating to come home to a place like theirs.

He handed her her drink and they toasted each other. She was conscious of his eyes upon her body. She looked boldly at him.

“When I had just met you,” he said, “and I bought you a Coke at the Thespian, I asked you what color your eyes were. They looked almost gray then. Now they look very green, really green.”

“They are green,” she said. It was always a point of dispute.

“Let me see,” he said, and he took her glass and set it down beside his own on the table beside the couch. He put his hand beneath her chin, so cleanly and strongly molded, and turned her face toward him.

“Yes,” he said, “they are green.” He put his arms around her and drew her toward him. She put her arms around his neck, as Janet had told her to. She was right; their bodies did fit together, and move together, and his hand ran down her back and pressed her close against him. The emotion was strong, overwhelmingly strong in the release from many months of solitude and want.

“Darling,” he said. “Darling.”

“Yes, Barry.”

He was unbuttoning the pink Brooks shirt and it fell from her shoulders as he put his arms around her and unhooked her bra. She was aware, very aware, of what was happening to her, but she wanted it. She wanted it; she had planned it, planned it long before he had ever thought of it, and she had asked him silently before he asked her, because she wanted it so much.

He took her by the hand into the bedroom, and he did not pull down the shades to cut off the light. She took off the rest of her clothes and she waited, lying on the bed in the marvelous luxury of her own young body, she waited for him.

Chapter 10

He was like a little boy as he slept in her arms. His face was young and relaxed. She didn’t want to sleep. That terrible, dragging exhaustion was gone, and her body and her mind were clear and at peace, marvelously alive and relaxed. She ran her hand through the hair that was long on his neck. It was very soft, as she had imagined it to be, and he did not wake up. His body was pale and hard, a young man’s body, sleeping with the peace of a boy. She was very happy. She was lost in her happiness. I have been loved, she thought. And this is my lover—she savored the word, formed it, lingered on it. An old and trite word, a word from historical novels, but the word was good to her.

She wished that he would wake up, so that he would love her again. Love. She had not known what it could be, and she would never live without it again. She had not known that she would know so much about love, the first time. The first time. She could never be as she had been before; she could never see life as she had seen it before, life with an entire sphere dimly seen.

He stirred, he was waking up as early evening came to the window. He kissed her shoulder; he was still half asleep, he probably didn’t know who it was, but she didn’t care. Then his eyes were open, and he looked at her for several minutes in the gentle silence.

He ran his hands along her body, along the ribs and the hips, pronounced but soft, and her body was relaxed. When he had first touched her body it had come alive where his hand had been.

“Court,” he said, and his face was troubled. “Court, I honestly didn’t know. If I had known—well, I’ve never done that. I’m not a very

moral guy, but I’ve never done that.”

“I wanted you to make love to me. I told you before, when you asked me, that I had never made love.”

“I didn’t believe you. You seemed to know so much, and in Schwab’s—I’ve never known a girl like you,” he said. “Honestly, this is no crap. You’re so quiet, and warm, and—well, almost poetic. It’s an odd word to use, but it suits you.”

“Barry, do me a favor. Don’t ever, ever say that you love me. Because that wouldn’t be true, and I don’t want you to feel you should say it.”

“No,” he smiled. “No, I won’t ever say that. I don’t love you, and you don’t love me, and there won’t be any pretending.” He put his head against her in the growing dimness. “But I don’t want you to go, darling. I don’t want you to leave me.”

“I won’t go until I have to, Barry. Ill stay here with you.”

She took him in her arms.

“You’re like a much older woman,” he said. “Not wanting to possess, not demanding anything from me. And yet you’re young, your body is young, your skin is young and fresh, and you trust as a young girl trusts.”

“Because no man has ever betrayed that trust.” She saw the question in his face. “No, you never betrayed it, either. Of course I trust in you. I trust in you completely. I have to, anyway,” she smiled. “Because I don’t know anything. Because you’re really the first, the first I’ve ever kissed, as well as the first I’ve ever made love with.”

He smiled at her, “Yes,” he said, “you kiss like a little girl kissing good night. I’ll have to teach you to kiss.” Suddenly he remembered. “Court, won’t your mother be worried? Won’t she wonder why you’re not home?”

“Yes. Yes, I guess I’d better get back. It must be almost seven.”

“I don’t want you to go,” he said again, and he meant it. “But I don’t want you to get in trouble, either. You’ll have dinner with me tomorrow?”

“Why, Barry, I thought you were famous for never buying anyone a meal.”

“You’re something else again. May I take you home?”

“No,” she said hurriedly. She didn’t want him to see where she lived. “No, I’d rather you didn’t.”

“Then I’ll pick you up tomorrow.”

“No—”

He understood. “Ill pick you up at school, and we’ll swim, and then we’ll have dinner. I don’t want you to wander down here by yourself, like—well, I just don’t want that for you. I’ll pick you up, and I’ll take you to dinner.”

“Yes,” she said. “I’d like that.”

She got up and started to pick up her clothes. He got up, too, and he took her clothes from her. It had never occurred to him to do this before, but this was the first time, and he did not want her to do anything for herself. There would be many times, many years, of doing everything for herself in the love affairs that she would have. He did not want her to know the self-sufficiency now. He did not want there to be any mark of the tired and familiar love affair in the memory of this, her first. He wanted to treat her as something very special, which she was.

When she had left, the apartment was very still and empty. He poured out the now-warm martinis. Beneath the couch he saw a paperback Western novel. He picked it up in disgust and threw it in the garbage can. George. Ugly mementos of the thing in his life that made him hate himself, that made him feel he was not even the least that he could be, a man. He was an actor, an actor of talent, he knew that. But his talent did not make up for the fact that he was not a man. His talent could not justify his existence. He made himself a fresh martini and sat in the living room. He turned on a light because the room was now dim.

He had been a man with Courtney, by God. Her first. She chose him, this lovely and talented young woman. He was not a man with the others, he was a gigolo. A gigolo. But today, this afternoon, he had been a man. He wondered if she knew. She must know, she knew so much. He wondered how he had been able to rise above himself this afternoon. He wondered where he had gotten the courage to make love to her, to take the chance of failure. She knew so little. He wondered if he had been good. He could teach her, though, he could teach her a great deal, because she knew nothing. And she had chosen him. Why did he make this drink. This drink, this liquor, this Western pocket book. This lovely young girl.

“You’re home late this afternoon, Courtney,” her mother said to her as she came in.

“Yes,” she said.

“What did you do, take a walk?”

“Yes,” she said. “I took a walk.”

“I worry about you when you’re not home by dark.”

“It’s just barely dark,” she said. “It got dark a little while ago, just a little while ago.”

“It’s a lovely evening. I don’t blame you for taking a walk.”

“It is a lovely evening,” she said.

“Are you hungry after your walk?”

“No,” she said.

“I think you ought to eat some dinner.”

“I’m kind of tired,” she said. “My walk relaxed me, and made me sleepy.”

“I suppose so. Well, I certainly can’t force you to eat dinner. Your walk seems to have done you good. You should do that more often. You don’t look as drawn and strained as you usually do after school.”

“Yes,” she said, “I think I will do it more often. Is it all right, Mummy, if I have dinner at a drugstore somewhere tomorrow night, for a change?”

“I don’t see why you want to eat at a drugstore.”

“Well,” she said, “it was so nice, just walking by myself. The streets are lovely in the evening. I thought I might go to a movie tomorrow night, after dinner—if it’s all right with you.”

“I don’t like you spending so much time by yourself. It’s not good for you.”

“Well, as a matter of fact, Mummy, one of the boys in my Latin class asked me if I wanted to have dinner with him and go to a movie.”

“Why didn’t you tell me? I think that’s wonderful. I’m so glad to see you starting to have dates.”

“Well, I don’t know, I—”

“Silly child, did you think I would feel you should stay here with me?”

“I guess so,” she floundered.

“No, I’m glad to see you having some sort of social life. I’ll be fine here. You know,” she smiled, “I spent many years by myself before you were ever born.”

“Thank you, Mummy.”

“Just be home by midnight, because you have school the next day.”

As Courtney took off her clothes and got into the bed beside hers, Sondra smiled to herself. What a thoughtful child. She put the world on her shoulders. She was afraid to tell me she had a date because she thought she should keep me company. What a wonderful daughter.

Chapter 11

She went to Barry’s apartment the next day, and they swam in his pool, and they lay in the sun, and she looked over at him many times, pleased and warmed by the thought that she knew the body within that bathing suit so well. They went to dinner at a steak house in downtown Los Angeles, a wonderful place. They did not eat in Hollywood because they did not want anyone who knew them to see them together. Then they went back to the apartment and had a drink, and they made love in the soft evening and it rained quietly and steadily outside the room.

The early winter passed in the newness of their love. Courtney developed a friend at school with whom she often stayed overnight, and her mother understood the fact that she never brought her friend home because she was embarrassed by her surroundings.

Courtney wondered what she would do when Christmas vacation came, how she would explain being out of the house all the days that she wanted to spend with Barry. Somehow, a week after vacation began and Courtney had spent many days sitting in the room reading, her mother’s efforts paid off and she got a small part on a soap opera as a temporary replacement for an actress who was taking a two-week vacation. It was a sharp come-down for her, and a severe blow to her already wea

kened pride, but it enabled her to pay back a little money to Al. More important for Courtney, it kept her out of the house during the day so that she could see Barry.

Sondra wondered what was happening to Courtney. The girl was so distant, with a new sort of distance. The world that she kept within herself seemed to have grown completely out of proportion. It was difficult to talk to her, even simple conversation. For the first time she seemed to have little interest in her mother’s fortunes, and she accepted her new job with little comment and no celebration. She took Courtney’s distance as an indication that the emotional problems which had begun to show themselves at Scaisbrooke had become aggravated by their relative poverty, so unfamiliar to Courtney. She was worried by it. Although Courtney seemed happy these days, it was a happiness which grew from her inner world, and it did not reassure her mother.

Courtney had learned from Barry. He was a good and gentle teacher. Everything she knew, even the simple act of putting her arms around him, she had learned from him, and she no longer kissed him as a small child kisses goodnight. She had been taught by an older man, an actor, as she told Janet she would be. “I want to be charming,” she had said in that room at prep school. “I want to be charming, to give in a charming way and to love in a lovely way.”

Now that she was on vacation, he could not pick her up at school, so she had gotten into the habit of taking the bus down to his apartment. His apartment was as familiar to her as her own, and she often helped him clean it and cooked dinner for him. She liked that; it seemed to make her role as a woman a fuller one. He was pleased; he was always pleased when a woman took care of him.

She usually came down around noon, and Barry rushed as he walked down Havenhurst, because it was a quarter to twelve: He put the collar of his corduroy jacket high around his neck. There was a crispness in the air. It was the fourth of January. How quickly these two months had gone. He kicked the dead leaves on the sidewalk into the gutter. How different his life had been these last two months. Strange, the way he had come to accept Courtney’s presence in his apartment, in his life. Of course they weren’t in love with each other, but there was a fondness and an ease which was impossible to maintain whenever love played a part in a relationship. Only companionship, and making love. And Christ, she was good, for a kid who didn’t know anything. It was a lovely life.

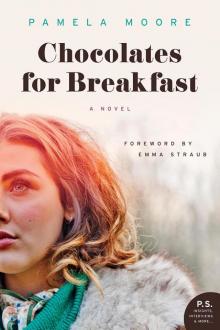

Chocolates for Breakfast

Chocolates for Breakfast