- Home

- Pamela Moore

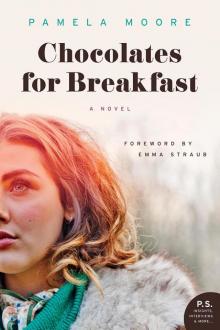

Chocolates for Breakfast Page 17

Chocolates for Breakfast Read online

Page 17

“It’s good to see you again, Mrs. Parker. You’re looking very well,” Courtney managed to say.

“David,” Mrs. Parker addressed her husband, “isn’t it nice to have Courtney with us.”

“Mmm-hmm,” he said, not moving from his chair. “How have you been, Courtney? Janet tells us that you’re going to a tutor in the fall.”

“Yes,” Courtney answered, “Mummy thought it would be good for me to have intensive schoolwork without all the rules I had at Scaisbrooke.”

“You know,” said Mrs. Parker with her head to one side, “I was saying to my husband that it might be a good idea for Janet to go to a tutor, rather than going back to that school she went to last year, because she didn’t seem to be very happy there.”

Janet laughed. “They just sent Daddy a letter saying that I might be happier somewhere else, and indicating that they might be happier, too. The polite axe.”

“It might be a very good idea,” said Courtney.

“We’ll have to look into that, won’t we, David?” Receiving no response, she continued, “What is the name of your tutor, dear?”

“Mr. Bigelow,” Courtney answered. “I’ll write it down for you.”

As she wrote the name and address of her tutoring school, Courtney looked over at Mr. Parker. What a strange, angry man, she thought. He looked very sorry for himself, sitting with his glass of bourbon. She remembered that Janet said he was worse when Mrs. Parker was home, that the rest of the time they had a sort of understanding, but when the third person entered the house his rages and his crying jags were more frequent. “I hear him getting up at five in the morning,” Janet had said, “and when I go into the kitchen in the morning there is almost always an empty fifth of bourbon on the counter.”

The maid came out of the kitchen.

“Dinner is served, Mrs. Parker,” she said as though unfamiliar with the phrase and her new mistress.

“Thank you, Ann,” said Mrs. Parker. “I do hope there is enough, Courtney. Janet told us at the last minute that you were coming and I did wish she had given us a little more warning, but she is so vague about these things, springing guests and parties on us without any warning. I do wish she would be more considerate of Mr. Parker and myself,” she said to Courtney in a confidential tone.

“Court, do you want to wash up or anything—in other words, go to the john?” asked Janet.

Courtney was enough at home in the Parker household so that she would have excused herself had she cared to, and she sensed in Janet’s unnecessary remark that Janet had something she wanted to tell her.

“Yes, I think I will,” said Courtney. “Please excuse us.”

When she entered Janet’s room, Janet closed the door and took a letter from the jumble of clothes in her top drawer.

“It’s been so long that I haven’t had a chance to tell you anything,” Janet said. “I’ve been having a thing with this really great guy, Marshall Richards, for weeks now,” she explained. “We’re madly in love, and he wants to marry me and all, and Daddy can’t stand him—he’s a really bad actor—bad news all the way—and he wrote me this letter from Newport last week.” She opened the letter. “This is the part you’ve really got to hear. ‘I hope that your father, that Babbittesque caricature of Samuel P. Insull, is sufficiently steeped in drink so that the next time I see you we won’t have another scene like the last.’ ”

“Very amusing,” Courtney said, “but what is the point of all this?”

“Well, I’ve suspected for a long time now that Daddy has been reading my mail, so I stopped leaving letters around the house. Last night though, when I looked in my drawer for this letter to get Marshall’s address, it wasn’t there, and this morning it had somehow returned. There’s a whole lot more in the letter, too, about my body, and how much he loves me, and all that.”

“This is all your father needs,” said Courtney.

“Well, he knows about me already, because once when we were having an argument I threw it up at him because I knew it would make him mad. But the thing I’m glad about is that I caught him in the act this time. So at dinner I want to let him know that I know he’s read the letter. That’s why I wanted to tell you before dinner,” Janet said. “Now we’d better go out so we don’t hold up dinner. Daddy is drunk as a lord,” she added as they went out the door.

Courtney and Janet took their appointed places at the dinner table, beside each other. The maid brought the first course, and they ate in strained silence. Mr. Parker was contemplating the centerpiece with a fixed and moody gaze, and Mrs. Parker was nervously alternating her food with sips of water, because she drank only one glass of sherry, never more or less, a day. Mr. Parker’s fresh glass of bourbon was beside him.

“How are your parents, Courtney?” asked Mrs. Parker in an attempt at conversation.

“They’re fine, thank you.”

“I would like to meet them some time. They must be very talented people.”

There was another agonizing silence as the first course was cleared and the soup brought.

“Daddy,” Janet said suddenly, “who was Samuel P. Insull?”

Mr. Parker fixed his gaze upon his daughter.

“Why do you want to know?”

“I ran across his name in a book,” Courtney said hastily, “and I asked Janet who he was. She thought you might know.”

“He was a very great man,” Mr. Parker answered gravely.

“But what did he do?” asked Janet.

“He controlled utilities in Chicago.”

“What was he like?” asked Courtney.

“A great public benefactor,” Mr. Parker said solemnly. “He gave his fortune to the Chicago Opera. A very generous and great man. A man who should be the model and inspiration for any businessman,” he continued.

Courtney was delighted. Knowing the game they were playing, Mr. Parker was extolling the virtues of the Chicago tycoon. He was really getting quite worked up, she thought as she listened to him, quite personally involved, as though he were defending himself against his daughter’s thrust.

“Yes, a very great man,” Mr. Parker repeated, taking another sip of his drink. “He had very little education, Samuel P. Insull, but he never forgot where he came from, and how he got to where he was. That’s a thing a great many people overlook,” he went on. “Janet with her debutante parties and her friends and her snobbery, she’s forgotten the value of hard work. Hard work, and humility. That’s why she can have all these things, because I worked so hard. Started as a messenger in the firm I work with, just a clerk when her mother and I were married, worked my way up. My own hard work, humility, and God’s help.”

Courtney was beginning to get a little embarrassed by the man’s alcoholic intensity. Their game was getting out of hand.

“God’s help,” he repeated. “Young people these days forget to thank God. To thank God for what He has given them, to respect their parents and fulfill their obligations. Ungrateful, the whole generation. Worthless.” He started to weep quietly as he talked.

Courtney said nothing.

“Now, David,” said his wife in agitation, “don’t upset yourself.”

He turned to her angrily. “Shut up.”

There was a silence broken only by Mr. Parker’s heavy breathing. He blew his nose loudly. Courtney looked at her dinner with fleeting distaste.

“You read that letter.” Janet broke the silence. “You went into my drawer and you took out a letter written to me, and you read it.”

He didn’t answer.

“You know you had no right to do that,” she said triumphantly. “And it was because you read that letter, because of what it said about me and the boy who wrote it, that you cut a hundred dollars of my allowance this morning. You weren’t fining me for coming in late last night. You were taking almost half of my allowance, because that was the only way you knew of hurting me, because you knew I didn’t care what you said or thought of me any more. The only hold you have over me is

money, and you know it. You know that’s the only reason I stay in this house, because the food and the bed are free!”

He looked up in fury, struck in his most vulnerable point.

“Yes, I read that letter,” he said. “I have a right to know what you’re doing, as long as I pay the bills. I have a right to know what everybody else in New York seems to know, that my daughter is nothing but a whore!”

They knew how to hurt each other, these two.

“Sure I sleep with boys!” Janet was almost shouting. “What do you expect me to do? At least they care what happens to me, at least I know I’m wanted. Do you expect me to stay in this house at night, when all I get is abuse from a drunken father? Do you think I feel this is a home?”

The maid came and cleared the dishes, bringing the main course unnoticed. Mrs. Parker had started to cry, and got up hastily, running into the bedroom. Courtney was very hungry, and tackled her dinner with relish.

“You can leave,” Mr. Parker was saying. “You can leave whenever you feel like it; you’re eighteen. I’ll be glad to see you go. How do you think I feel when I sit here alone at night and I know you’re off sleeping with some drunken college boy?”

“Just the way I hope you feel. Just the way I want you to feel.”

The lamb chops were a little too well done, Courtney noticed.

“All I worked for all my life,” he shouted. “I wasn’t working for myself, I was working for you, and your mother—”

“Crap,” said Janet calmly.

“—you and your mother, and you drive her into a sanitarium with your promiscuous life. To see you a laughing-stock, someone mothers and teachers point to—was that what I worked my fingers to the bone for? Was that what I spent my life for, to give you enough money to sleep with college boys instead of poorer juvenile delinquents?”

“Who are you to criticize me, you, an alcoholic, a person I am embarrassed to have my friends meet. What kind of a father do you think you are? What do you think you have ever given me? Money. Hell, I can make money, I can marry money, I can get money in a thousand ways; it doesn’t mean anything, if I live in a place I can’t bring my friends to. I might just as well live in a tenement as Park Avenue.”

With dogged determination, Courtney finished her dinner. She wanted desperately to leave, to flee this scene as Mrs. Parker had, but her loyalty to Janet made her stay.

“Then get out. Then leave, if I embarrass you so!”

Janet looked at him, suddenly silent and thoughtful. Courtney wondered what she was going to say.

“No,” Janet said quietly. “No, I’m not going to leave. You owe me something as your daughter. You haven’t given me anything but a family I’m ashamed of and a house I hate. I’m going to make you give me something. I’m not going to leave. That would be the easy way out for both of us. I’m going to stay, and you’re going to support me until I’m through high school. I’m not going to let you off that easily.”

Mr. Parker lurched from his chair in fury. He gripped the glass in his hand and threw it at the girl. In his anger it missed her and hit above her head on the wall, shattering and spilling its contents on the thick carpet. He was defeated, out-bluffed, and he knew it. He knew that his impotent devotion to his daughter, so like him in her combativeness, unafraid of him or anyone else, and his own terrible loneliness would not permit him to drive her from his life. She had beaten him. He left, defeated, as she sat in triumphant silence watching him. He took the bottle of bourbon with him and a new glass, and walked out to the living room.

His wife was in the bedroom, undoubtedly in hysterics at this evidence of the dissolution of her family, and the fury of her husband and the daughter who was so like him. It was the fury and self-destruction in each of them that she could never understand, and it frightened her. She had locked the door to her bedroom, locked herself in as she had for so many years.

There was a silence over the whole apartment. The maid stood in a corner of the kitchen, and as she realized that the terrible fury had once more abated, she started to wash the dishes, humming tunelessly to herself because the sound reassured her.

It was Janet who spoke first.

“My dinner isn’t cold, thank God.”

When they had finished dinner, Janet went into her room and put on her make-up while Courtney put on some lipstick. Janet put on some Kenton records and turned up the volume loud to fill the silence of the apartment. Then they left, carefully avoiding the living room. As they went out Janet tried her key in the front door.

“That’s good,” she said. “He hasn’t changed the lock again. Whenever Daddy is mad at me,” she explained, “he changes the lock so I will have to ring the bell to get in, and he can know what time I come home. Then I have to get a new one made. The locksmith around the corner and I are great buddies by now,” she grinned. “But I guess Daddy won’t get a chance to change the lock until tomorrow.”

And they got in a cab and headed down Park Avenue to their cocktail party.

They were greeted at the door by a young man in Bermuda shorts and matching gray flannel jacket, and they walked into an enormous living room filled with young people. Drinks were thrust into their hands and, armed, they advanced into the center of the horde.

“Dapho,” shouted Janet as she rushed over to a young girl in black, “how great to see you. Did you and Al ever get back from that party on the Island last week? Someone said he found Al marooned in Oyster Bay—”

“Yes,” someone was saying at Courtney’s elbow, “the Count lost his job on the Street; they got tired of his being either bombed or hung over—”

“He got out of the army because of cirrhosis of the liver,” a young man was saying. “The doctor really flipped, at the age of twenty.”

“And, my God, did they make out, right in the living room, which was all right except that the girl who used to be mad for him was right there, and here this was practically a seduction, she was really throwing the make on him—”

“She wouldn’t let you go out for a week? Oh, is your mother a bitch, too?”

“Oh, my date passed out, as usual, so they won’t let him in any more—you know, some gun-happy cop pulled a gun on him once when he tried to slug the cop, that sobered up Davidow, thank God, so—”

Through the milling conversations Courtney, seeing that Janet was occupied, made her way to the kitchen to put a little water in her Scotch. After all, this was going to he a long party.

The only other person in the kitchen was a tall young man in gray flannels, wearing a somewhat detached air, who was fixing himself a martini.

“Hello,” he said, “we haven’t met, but as you’re the only other sober person I’ve seen, I think we should make each other’s acquaintance. I’m Charles. Cunningham.”

“Courtney Farrell,” she said. “Everyone else seems to have arrived before us and gotten an edge.”

“Us?” he said, gently stirring the martini. “Did your date get lost in the throng?”

“No,” she reassured him. “I came with Janet Parker.”

“Oh. Yes, Janet.”

“You know her?”

“Who doesn’t?” he said with a quick smile. “I see you have some of that abominable Scotch they are serving. Some remote brand that they forced on me when I came in. I couldn’t stomach it, so I’m making a martini. If you’d prefer one, there are about four in this shaker.”

“Yes,” she said, “perhaps I shall. I usually drink Scotch out of habit. A martini would be nice for a change.”

“Just leave your drink on the counter,” he said. “Someone will take it.”

Courtney made the quick appraisal of the young man that she always made of cocktail party acquaintances. He was tall and self-assured, and seemed somehow older than the others at the party. His hair was brown, lightened by the sun, his skin was tan, making his quick, easy smile more noticeable by contrast. His eyes were blue and direct, with the disconcerting quality of never leaving his companion’s face.

He had a slightly critical and self-contained air, the air of the observer. She decided that he was worth staying with, and accepted the martini that he handed her.

“You in school?” he said.

“Yes. And you? Yale, I suppose. Most of the people here are.”

“I went to Yale,” he said. “That’s where I met our host. I’m just finished with Harvard Law.”

“Oh,” she said. He was older, then. Probably about twenty-five. She liked that. “You’re not a member of the Crew, I see.”

“No,” he said with the smile which relieved the direct intensity of his expression. “No,” he repeated. “I like to drink, but I find no charm in passing out and getting sick all over my dates. The routine doesn’t appeal to me. I’m afraid I find being sober a little more enjoyable. I may be lost, but I refuse to be so blatantly lost.”

Supercilious, she thought. Although she agreed with what he was saying, she felt in his words a criticism of herself for being with these people. She didn’t say anything.

“Is Janet a good friend of yours?” he asked.

“Yes,” Courtney answered. “Since we were in Scaisbrooke together.” She was aware that whenever she said she was a good friend of Janet’s there was always a slight reaction, a sidelong glance, but she refused to deny Janet because of her notoriety.

“She’s a very game girl,” he said. “But game girls become tiresome. There are so many of them.”

“Say, you’re awfully critical, aren’t you?” said Courtney finally. “I might make a similar remark about youthful cynics.”

“All right,” he smiled. “Touché. How is the martini?”

“Excellent. And I am a harsh judge.”

“So am I. Of martinis and people.”

“I gathered that.”

“Well, it’s not that I’m cynical,” he said. “I am probably too much of a perfectionist. I set high standards, for myself, and the people around me. It doesn’t endear me to people,” he smiled. “But there’s really nothing I can do about it. Say, what about going into another room? It’s awfully hot in here.”

Chocolates for Breakfast

Chocolates for Breakfast